How to play Rock-Paper-Scissors

Rock-Paper-Scissors is a game played to settle disputes between two people. Thought to be a game of chance that depends on random luck similar to flipping coins or drawing straws, the game is often taught to children to help them settle arguments between themselves on their own without adult intervention. However, the game actually can be a game that has an element of skill that requires quick thinking and perceptive reasoning.1

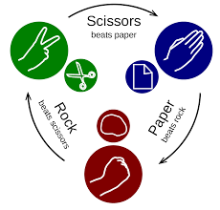

The game is played with three possible hand signals that represent a rock, paper, and scissors. The rock is a closed fist; paper is a flat hand with fingers and thumb extended and the palm facing downward; and scissors is a fist with the index and middle fingers fully extended toward the opposing player. Rock wins against scissors; paper wins against rock; and scissors wins against paper. If both players throw the same hand signal, it is considered a tie, and play resumes until there is a clear winner.

The hand signals are given simultaneously by both players. The ritual used to get players in sync with each other so they can deliver their throws simultaneously is called the prime. This action requires retracting the player’s fist from full-arm extension towards the shoulder and then back to full extension. To ensure a fair match the players must be in sync with their primes. Players must determine before play how many times they pump their arms during the prime phase, usually two or three times before the final delivery of their throw.2

Variations of Finger-Flashing Games from Around the world

Finger-flashing games have been known to exist since ancient times, however, the origins of the game remain obscure. The earliest known reference is found on a wall painting in a tomb at the Beni Hasan burial site in Egypt that dates back to around 2000 B.C. Centuries later on a Japanese scroll the game was also found. Versions of the game are found in cultures around the world. It is still very popular in Japan, where it is called jan-ken or jankenpon.3

In North America the game has also been called Rochambeau or Roshambo. Many have tried to attribute this name of the game to French army general Comte de Rochambeau who fought with General George Washington during the American Revolution. However, in-depth research has not been able to make any association with the general and the name of the game.

Although there is no mention before the early 20th century of the game in America, a similar game called Odds and Evens was mentioned in the biography, Life of Samuel Johnson, in the late 18th century in England, and would very likely have been brought to America as immigration expanded into the New World.4 To play this game, each player decides if they will be either “odds” or “evens” and then both clench their fists, count to three at the same time, and open one hand extending one or more fingers. Combining the number of extended fingers on both players’ hands determines the winner: if an odd number, the player who declared “odds” wins; if an even number, then the “evens” player wins.5

The earliest mention of variations of Rock-Paper-Scissors in America is found in a compilation of children’s games in the Handbook for Recreation Leaders written by Ella Gardner, who was a recreation specialist with the Children’s Bureau in Washington, DC, published in 1935. Other references soon appeared in other publications in the late 1930s. The game had an upsurge in popularity after World War II from articles in the Army’s Stars and Stripes newspaper, written by army reporters stationed in Japan during the U.S. occupation of the country. Apparently unfamiliar with the game, the reporters described the game as a version of Odds and Evens. The game began to be mentioned often in books, magazines, and newspapers from that time on and became firmly embedded in American culture.6

The game Rock-Paper-Scissors has become a great tool on children’s playgrounds. Playworks, an organization that works with inner-school children at their schools, introduces recess games to the children and empowers them to run their own games and settle any disputes quickly with a game of Rock-Paper-Scissors. Their success with conflict resolution is achieved because children quickly learn that “getting along is more fun than fighting.”7

Not just for children, Rock-Paper-Scissors has become popular with adults who compete in championships for large cash prizes. Some competitions have had large corporate sponsors and have been televised. In 1995, two brothers, Doug and Graham Walker, started a website devoted to Rock-Paper-Scissors. Named the World Rock Paper Scissors Society, the website was meant to be a whimsical tribute to a game they loved, but their website quickly exploded with followers, and they hosted their first championship in 2002 with hundreds of players.8

When children play the game, their choices are random and usually not calculated. However, when adults play, the players tend to reason how their opponent will play making the game more like a mental game of poker or chess. Good players utilize strategies to read their opponents’ body language and also to bluff them into thinking they know what hand signal they will throw. Often good players predetermine their initial throws and may plan to throw a string of “gambits,” which are a series of throws like Rock-Rock-Rock or Rock-Paper-Paper.9

Good players recognize that amateurs tend to have certain patterns in their play. Men tend to throw a rock for their first throw, while women will often throw scissors. Amateurs don’t usually repeat the same throw more than twice in a row, believing that it wouldn’t seem random. If a player loses, he is more likely to switch to a different throw the next time, and some unconsciously will throw whatever hand signal beat their last throw. Using careful observations and strategies make Rock-Paper-Scissors more of a game of skill than just a random game of chance.10

- 1. Carlisle, Rodney P. Editor. Encyclopedia of Play in Today’s Society. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. 2009. p. 603.

- 2. “Game Basics: How to Play – Quick Start.” World RPS Society. < http://worldrps.com/game-basics/ > 1 Sep. 2016.

- 3. Schwab, Katharine. “A Cultural History of Rock-Paper-Scissors.” The Atlantic. 23 Dec. 2015. < http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/12/how-rock-paper-scissors-went-viral/418455/ > 1 Sep. 2016.

- 4. Buescher, John. “Rock Paper Scissors.” National History Education Clearinghouse. < http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/23932 > 1 Sep. 2016.

- 5. “Game: ODDS & EVENS.” University of Waterloo. Elliott Avedon Virtual Museum of Games. < http://gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca/VirtualExhibits/Brueghel/odds.html > 1 Sep. 2016.

- 6. Op. cit., Buescher.

- 7. “How to play and teach Rock Paper Scissors.” Playworks. < http://www.playworks.org/playbook/what-is-a-great-recess/how-to-play-and-teach-rock-paper-scissors > 2 Sep. 2016.

- 8. Op. cit., Schwab.

- 9. Mayyasi, Alex. “Inside the World of Professional Rock Paper Scissors.” Priceonomics. < https://priceonomics.com/the-world-of-competitive-rock-paper-scissors/ > 2 Sep. 2016.

- 10. Poundstone. William. “How to always win at rock, paper, scissors.” The Telegraph. 1 Sep. 2014. < http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/thinking-man/11051704/How-to-always-win-at-rock-paper-scissors.html > 2 Sep. 2016.